How to *finish* your side-project

July 15, 2019

I’ve read some good posts about the importance of having side projects, and I agree, they are important. And fun. I want to talk about finishing your side project. Part of the reason I chose to work part-time is so I can have more time for my side projects. I’ve started many projects. I’ve actually finished only a small fraction of them. Here’s what I think made the difference.

Definitions

But first, some definitions.

PSP - Personal Side Project

- Personal - you’re doing it alone, or with a friend

- Side project - you’re not doing it full time, and if full time, not for a long time (if you’re dedicating the next 5 years of your life to work on it, then it’s not a side project, it’s your startup.)

“Finishing”

- For our purposes, finishing your PSP is shipping a working version out there (an MVP if you will) for people to use. In reality, a product is never really “finished”. Apps constantly change and evolve. Your product might hit off and you’ll decide to continue working on it for 10 years. Or you might release it and realize it’s worthless. But for our purposes, finishing is getting it out there for people to start using.

The danger

Pop quiz: what’s the biggest danger your PSP faces?

- a. Being a bad product

- b. Having bad design

- c. Having 0 traction

- d. Making you so much money you go insane

All real dangers no doubt, but I would argue that the real danger your side project faces is abandonment. Why? Because you have limited time, energy and motivation. No matter how enthusiastic you are about it now, your motivation is bound to wane. The more time it takes to finish, the more likely you are to abandon it.

The biggest danger your side project faces is abandonment

Why you should finish your project

But why should I finish it? Isn’t it enough to revel in the joy of creation? Sure, you’ll learn a lot from everything you do, and might have a lot of fun in the process. But I’ve noticed that no matter how much fun I have developing, an unfinished project impinges on my psyche. Like an unrealized dream. Like that girl/guy you thought liked you, and you never made a move, and you’ll never know if it could’ve worked. But the main reason to finish a project is that it gives you more motivation to keep working on it. Circular argument? Perhaps… Let’s see how that works.

Motivation and traction

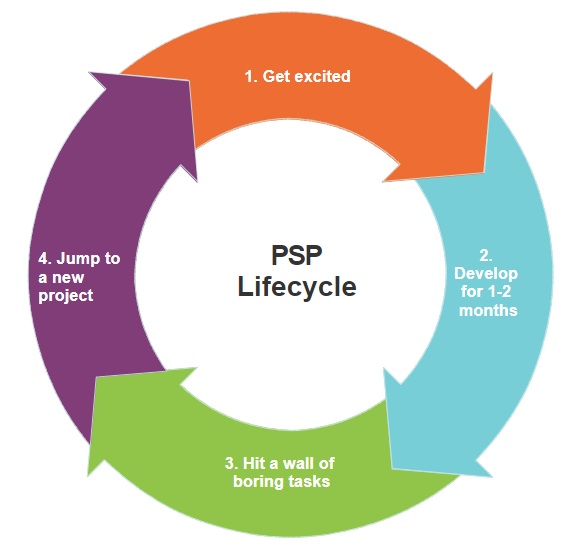

I’ve noticed a recurring pattern in my motivation to work on something.

- I get super excited about something, and start working on it.

- Work on it for about a month, maybe two.

- The project grows in complexity, I can’t get the design right, progress slows. I get bored.

- I get super excited about something else and I’m ready to switch. This is the stage I usually abandon the project, telling myself I’ll get back to it later, but it rarely happens.

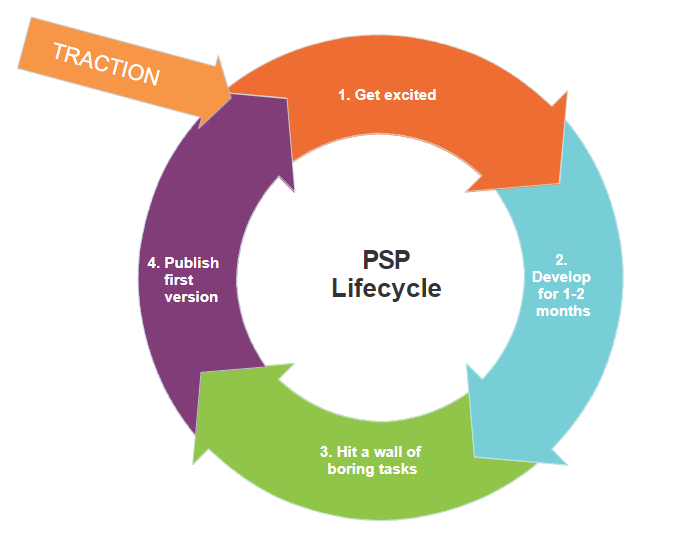

What breaks this pattern, and breathes new air into a project, is traction. When you see your product out there and people using it, you get motivated. And for good reason. When people are using your product, you know it’s viable, and you know it’s worth your time to continue with it. If not, you know you tried and can continue on wholeheartedly to other endeavors. Also, moving on at this stage doesn’t kill your project, because it’s out there, and can start gaining traction with time, while you work on something else.

You never know

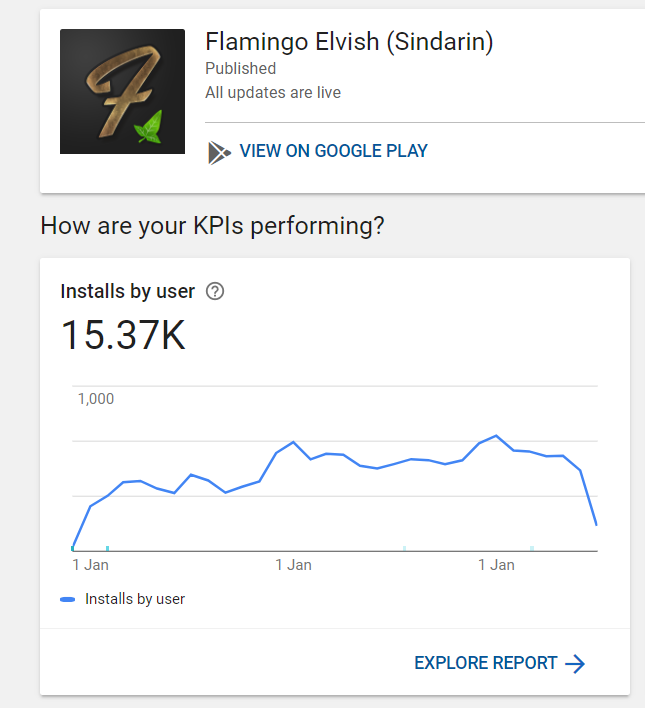

Your project could reach more success than you think, or even become a source of income. You’ll never know if you don’t get it out there. When making the language learning app Flamingo French, I thought it would be mildly successful. It wasn’t.

But then we had the idea to test out some languages that don’t actually exist, and the results were surprising:

I would never have guessed this when first starting the project. The point is, you never know until you get it out there.

Better estimations - The 40% rule

Until you finish your project, you’re likely to grossly underestimate the work required to actually finish it. You think to yourself “it’s basically done, just need some finishing touches”. Those finishing touches can take more time than building it!

After I “finished” building my morning pages app Blurrish (built with electron and vue), I decided to upload it to Apple’s app store. It was already working on mac, so I thought it would take a couple of hours to publish to the app store. It took me a week! (I had to re-write large parts of my code due to sandboxing and app signing problems). I could only have learned this by actually trying to publish the app to the store.

I will paraphrase David Goggins here:

Whenever you think the project is done, it’s 40% done.

You learn this by experiencing it.

How to finish your side project

Now that we agree that we want to finish it, let’s see how. The most important part of finishing you project is choosing what not to do. The best way to finish your project is by constraining it.

Eu-constraints

Constrain yourself so you don’t strain yourself

Making a product is a form of creation. Whenever you’re creating, you’re bringing something into existence that wasn’t there before. And when you do that, you need to choose from an infinite number of options. This is called the blank page problem in the writing world. And that’s the hard part of creating.

Constraints are crucial. Having a good set of constraints limits the infinite number of possibilities, and even makes you more creative.

Because we usually perceive constraints as negative, let’s add the greek prefix “eu” (as in euphoria, not the European Union), to remind ourselves that they’re good.

Source: wiktionary

Luckily, we have some constraints built-in to the definition of a PSP, and this is exactly what forces us to be creative. I like naming things in order to remember their importance. And I also like acronyms. Enter SCRUF.

SCRUF - Simple, Cheap, Re-Using and Fast

The SCRUF method (never miss an opportunity to invent a new acronym) shows the most important constraints for a side project you’ll finish:

1. Simple - become a “feature minimalist”

It’s hard to build software. The bigger it is, the harder it is. As developers we have a tendency to under-estimate the time it takes to build something. NOT developing features you think you can develop is one of the hardest things for developers. Take yourself by the scruff of your neck and learn to say no to features! For every feature you add, coding it is just the tip of the iceberg. 90% of the time it will take is in the complexity it adds to the rest of the system, the bugs it will create, the UI problems, etc. Practice feature minimalism and ruthlessly cut away any feature that’s not essential.

2. Cheap - burn rate will kill your project

The greater the burn rate of each product you publish, the more likely you are to pull the plug on it prematurely. Use free services, or services that will only start costing when your product is generating income. I think 10-20$ per year burn rate is a good number to aim for. Basically only pay for the domain name (if you need it), and use free stuff for the rest. The goal is to have multiple projects, that can run long enough to see if they stick. Maybe you think paying 20$ a month isn’t a lot, but if you have 5-10 side projects running, it can add up. Some suggestions for cost cutting:

- No dedicated email server / GSuite. You can configure GMail to send and receive emails from you@yourdomain.com.

- Use Netlify over Heroku for hosting your public facing website - SSL is free.

- Domain - get the cheapest version - shouldn’t cost more than 10-20$.

- Start paying for upgrades and premiums only when you’re making profit.

3. Re-Using - reinventing the wheel is a DRY violation

DRY - Don’t Repeat Yourself, the most fundamental rule of programming. Maybe even the definition of programming. Don’t repeat your own logic, and don’t repeat other people’s work unnecessarily.

A few suggestions:

- Make it cross-platform. Use cross-platform libraries like cordova, react native, or electron. Building and maintaining two separate code-bases for Android and IOS, or Mac+Windows+Linux is a huge waste of time (and a huge DRY violation).

- Use a UI framework - instead of inventing css for UI components that many people have used before, use a UI framework. Unless a new amazing UI is a core feature of your product, it’s better to spend time in other areas than css. Does your app really need that custom CSS you’ll spend a week creating? Do your users really care?

-

Starter project - Spend time on finding a good starter project e.g. Vue project running in a Cordova app with Quasar UI Framework. This will save a ton of time in scaffolding and creating a good dev process.

- Test the components and performance of the stack and UI framework on your TARGET OS before choosing.

4. Fast

For me, the time constraint is huge, and it’s a constraint you can easily let go of, because you’re in charge of your own time.

I aim for a product I can ship in about one month - calendar time. This is for first version, and is mainly in order to dictate the size of the project and what features your first version should have. It’s OK (and beneficial) to change the idea a bit in order to fit the size of the project to this time frame.

Why calendar time? Because that’s the determining factor in how motivated you’ll stay. If you have 3 hours a day to work on it, you can do more. If you have 3 hours a week, you can do less. Choose the size of the project according to the time you have to work on it, and keep the total amount of calendar time constant. I’ve noticed that the time frame of a month works well, and obviously this will vary from person to person. Part of the benefit of making things on your own is that you learn to know your own process and how your motivation works.

A point about deadlines: I don’t believe in setting arbitrary deadlines for yourself. This has never really worked for me. You can get into a habit of elimination by keeping a time frame in mind, but an arbitrary date seems redundant. It is a form of constraint though and it might work for you. Try it.

You need to be ruthless to be fast. Cut anything that’s not 100% necessary for a useable first version. Good examples are:

- Cut server side. Making your app serverless will not only save about 50% of dev time actually writing and debugging server code, but will also make your client code much simpler. I don’t know if there is any data to support this, but I would estimate that you cut about 70% of the workload if you can make your project serverless (I don’t mean serverless.com, but actually serverless. As in no servers at all). This won’t always be possible, but remember that hard constraints make you be creative and might end up giving your product an edge over the competition.

- Cut user management / login systems - Is having a user profile a core feature your app will fail without? If not, cut it. You can always add it later.

- Cut unit tests. Yes, I just said that. Shoot me. Unit testing is not gospel, and in our case the overhead is not worth the benefit. (Unless your side project is a temperature-regulating app for nuclear reactors. Then please write unit tests.) As your project grows in complexity, and as your team size grows, you might want to add unit testing or another form of automatic testing, but for now, skip it. If SO can do with very few unit tests, so can your small, simple side project. Of course, if you have a super critical piece of code you can protect it from regressions or bugs with unit tests. I did that for user’s journal encryption logic in Blurrish, because corrupting journal entries is unforgivable.

Summary - High level work process

- Choose a project, using SCRUF to ensure it’s “finishable”. Don’t multi-task here, one project at a time in phase 1.

- Publish a first version. Get it out there.

- Marketing, analysis, feedback - This can go on while starting the next project.

- Maintain, expand, or discard - Is this project worth working more on? If so, great. If not, leave it and move on to more interesting things.

- Repeat

Do you have side projects you’ve never finished? How long does it usually take you to finish a side project? Would love to hear feedback / thoughts :)